Quote of the week

[T]he moral point of the matter is never reached by calling what happened by the name of ‘genocide’ or by counting the many millions of victims: extermination of whole peoples had happened before in antiquity, as well as in modern colonization. It is reached only when we realize this happened within the frame of a legal order and that the cornerstone of this ‘new law’ consisted of the command ‘Thou shall kill,’ not thy enemy but innocent people who were not even potentially dangerous, and not for any reason of necessity but, on the contrary, even against all military and other utilitarian calculations. … And these deeds were not committed by outlaws, monsters, or raving sadists, but by the most respected members of respectable society.

Eichmann in Jerusalem: A Report on The Banality of Evil

A rethink on race?

In the 1980s the Weekly Mail (which later became the Mail & Guardian) every week published a column called “Apartheid Barometer” which catalogued the most absurd and insulting official excesses of the apartheid government. (The unofficial excesses – such as the killing and torturing of apartheid opponents – could, of course, not easily be documented, given the secrecy around these ostensibly illegal acts and given the censorship enforced by the apartheid state.)

This column provided information about which documents and books had been found to be “undesirable” by the rather sinister Censor Board in the previous week. ANC pamphlets, items which contained displays of dagga leaves, books and movies which contained soft and hardcore pornography and items “calculated to stimulate lust” like dildo’s and vibrators all made their appearance on the list.

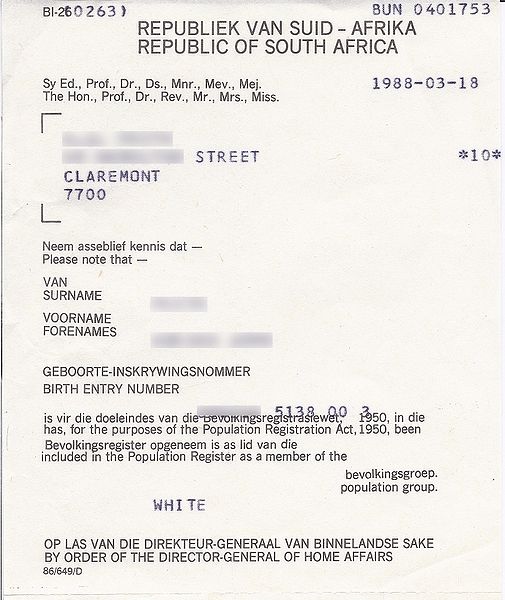

The most obscene section of the Apartheid Barometer contained information about the racial reclassification of citizens. Every week we read that so many “africans” had been reclassified as “coloured”; so many “coloureds” had been reclassified as “indians”; so many “whites” had been reclassified as “coloureds”. (These terms were amended from time to time: at first “africans” were classified as “bantus”.) Of course, the list hardly ever contained any mention of any “whites” being reclassified as “coloureds”, “indians” or “africans” because “whites” were privileged and no “white” person in his or her right mind would have wanted to stop being a “white” person.

This was all done in terms of the Population Registration Act 30 of 1950. The Act required every South African to be classified in terms of race and these apartheid race categories included “african”, “white”, “coloured”, “other coloured” or “indian”.

This was all done in terms of the Population Registration Act 30 of 1950. The Act required every South African to be classified in terms of race and these apartheid race categories included “african”, “white”, “coloured”, “other coloured” or “indian”.

The Act was amended often to try and make it more difficult to reclassify anyone as “white”, but the definitions used at one time included the following:

White person is one who is in appearance obviously white — and not generally accepted as Coloured – or who is generally accepted as White – and is not obviously Non-White, provided that a person shall not be classified as a White person if one of his natural parents has been classified as a Coloured person or a Bantu…”

“A Bantu is a person who is, or is generally accepted as, a member of any aboriginal race or tribe of Africa…”

“A Coloured is a person who is not a White person or a Bantu…”

Although this Act was finally abolished in 1991, the effects of this legally enforced racial system has not disappeared. How could it? After 300 years of racial social engineering, which was aimed at privileging “whites” vis-a-vis “other race groups” and of securing white privilege and social and economic domination, abolishing the legislation on which this racial hierarchy was built would not happen overnight. To some extent we all still suffer from this apartheid racial hangover.

Even if we wish to deny it, race hovers not far from the surface in private or other everyday settings: as an unspoken presence, a (wrongly) perceived absence or as a painful, confusing, liberating or oppressive reality in social, economic or other – more intimate – interactions between individuals or between groups of individuals. In South Africa we (still) cannot escape race.

It will take a concerted legislative, educational and societal effort to dismantle this system of racial hierarchy and race-thinking. That is why the Constitution mandates affirmative action and why legislation like the Employment Equity Act and the Black Economic Empowerment Act was adopted by the ANC government.

Without these legislative measures it would have taken hundreds of years to begin to address the effects of past racial discrimination. Even today, most “white” South Africans are absurdly privileged vis-a-vis most “black” South Africans. However, there is a price to pay for these legislatively mandated corrective programmes and we have to admit that there is a huge irony and a seemingly unsolvable paradox at the heart of this effort to dismantle the effects of apartheid race thinking, which have again been highlighted by the Jimmy Manyi scandal.

While South Africa has emerged from a period in its history in which the race of every individual played a decisive role in determining their life chances, allocating social status and economic benefits on the basis of race in terms of a rigid hierarchical system according to which every person was classified by the apartheid state as either “white”, “indian”, “coloured” or “black” and allocated a social status and economic and political benefits in accordance with this race, in the post apartheid era the potency of race as a factor in the allocation of social status and economic benefit has not fundamentally been diminished in our daily lives — despite a professed commitment to non-racialism contained in the South African Constitution, the founding document of our democracy.

The problem is that when the law deploys race to address the effects of past unfair discrimination and the ongoing dominance of an ideology of white supremacy, how can this be done without merely perpetuating the very apartheid race categories and the positions of privilege and hierarchical dominance of whiteness implied by it?

The problem is complex. On the one hand, the danger is that the deployment of racial categories in the law can have the effect of perpetuating and legitimising racial categories (and the assumed dominance of whiteness inherent in the deployment of such categories). By recognising these categories and by dealing with them as if they are a given — normal, essentialist, unchanging and unchangeable — and by failing to challenge the hierarchical assumptions underlying the deployment of these categories, the law can do immense harm — even in the name of wanting to do good.

Instead of helping us to move away from a hierarchically racialised society in which racial categories continue to exhort a powerful pull on the way in which we perceive and understand the world and how we perceive and understand ourselves and our relationships with those around us, the deployment of apartheid racial categories in law can contribute to the perpetuation of the very race-based hierarchy that is the cause of the “problem of race” in our society.

On the other hand, if racial categories are not deployed in legal discourse and in the legal provisions aimed at addressing the effects of past racial discrimination and the continued dominance of an ideology of white dominance, the law may well fail to address the effects of past racial discrimination and the ongoing problem of racism and racial oppression.

If the law insists that race is (or should be) absolutely irrelevant and superfluous, and that racial categories should therefore not be relied upon by the law (even when the law is aimed addressing the effects of past and ongoing racial discrimination and racism to achieve a society that truly moves beyond race — a society that treats individuals as individual human beings of equal moral worth regardless of any constructed differences), how can the powerful effects of past and ongoing racial discrimination and racism be addressed?

Would it not be true that if we insisted that race was irrelevant and superfluous, we would be endorsing and perpetuating the fiction that the characteristics, cultural beliefs and (often unexamined and silent) norms of the dominant white group are universal and neutral? Would such a “race-blindness” in the law not impose white dominance by erasing awareness of racial identity or cultural distinctiveness, given the fact that many South Africans still experience whiteness and white cultural practices as normative, natural, and universal, and therefore invisible?

Would this not negate any understanding of racial domination in terms of cultural or symbolic practices? And if one insisted on this fiction that race as a lived reality did not exist in South Africa or that it did not matter, would one not be denying the powerful effects of a pervasive racial ideology that continues to oppress and marginalised “black” South Africans? Would such a stance not require one to ignore the lived reality of a majority of South Africans who experience race as real and as oppressive?

We have to try and move away from the crude apartheid era race categories (as my colleague Zimitri Erasmus refers to them) while recognising that the effects of past racial discrimination and the effects of ongoing racism has to be addressed urgently. People like Jimmy Manyi, Kuli Roberts and Steve Hofmeyer seem quite comfortable with using these categories and they often use them as if these categories say something essential and true about the individuals who are categorised in terms of them: “coloureds” don’t have front teeth; “whites” are all racist murderers; “indians” are all devious; “africans” are all lazy farm murderers – you all know these stereotypes.

For me the starting point should be to recognise that these categories are the product of a specific history and that they cannot be used to predict how individuals who are said to slot into these categories will behave, what their attitudes will be, and who they are as individuals. When we use these categories for purposes of redress we should do so ironically and in a contingent manner. (That is why I place inverted commas around the terms when I use them: I wish to signal that I believe these terms are no more than crude and obnoxious descriptors which can never capture the full essence of each individual person supposedly described by them.)

Second, a more nuanced deployment of such categories in our law is required. Apart from these categories (which for the moment we have no choice but to rely on to help effect redress) we may want to add other factors when we decide whether an individual should be the beneficiary of a specific programme of corrective measures. The social and economic status of the individual and his or her parents; whether an individual is part of a first generation who has obtained secondary or tertiary education; whether an individual grew up in a rural area or in the city; whether the individual is monolingual or speaks several South African languages — these factors could all be used by our redress legislation along with race to counter the corrosive effects that the use of apartheid race categories might have on our entrenched racial assumptions and on the perpetuation of the racial hierarchy which is so well known from the apartheid days.

Maybe there are other ways to deal with these issues. Who knows? What I do know is that we need to continue having a conversation about what will work best. When I talk about a conversation I do not mean a shouting match in which individuals retreat into the laager of their own apartheid era racial identities and shout abuse at others who they perceive to belong to a different apartheid race category. In having this conversation it would be helpful if we could agree that it is important to take race and the need for racially-based redress seriously while also acknowledging that in doing so there is a danger that the use of apartheid era race categories will imprison us all in an apartheid of the mind — something that Steve Biko warned us against.

What is needed — to use the dreadful cliche — is “out of the box” thinking. In other words, we need to try not to follow the example of Jimmy Manyi, Kuli Roberts or Steve Hofmeyer. This we can only do if we have a real and open discussion about what race did to all of us in the past (and continues to do to us today) and how we can address the effects of race in the future; if we do not take part in the discussion as perpetual victims (of racism or of so called reverse-racism), but as equal, respectful human beings who believe and act like people who have the pride in themselves and the power to chart a new destiny that is fair and just for all — not just for those who belong to the same racial group we happen to believe that we belong to.

BACK TO TOP