Quote of the week

[T]he moral point of the matter is never reached by calling what happened by the name of ‘genocide’ or by counting the many millions of victims: extermination of whole peoples had happened before in antiquity, as well as in modern colonization. It is reached only when we realize this happened within the frame of a legal order and that the cornerstone of this ‘new law’ consisted of the command ‘Thou shall kill,’ not thy enemy but innocent people who were not even potentially dangerous, and not for any reason of necessity but, on the contrary, even against all military and other utilitarian calculations. … And these deeds were not committed by outlaws, monsters, or raving sadists, but by the most respected members of respectable society.

Eichmann in Jerusalem: A Report on The Banality of Evil

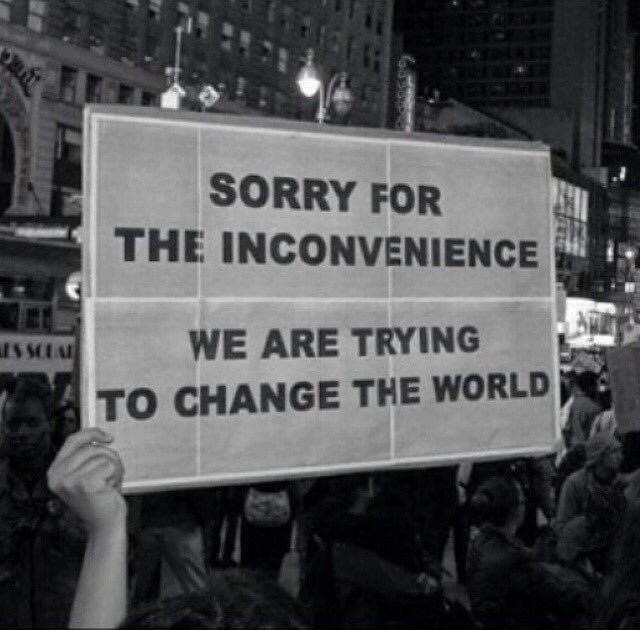

#FeesMustFall: On the right to mass protest and the use of force by police

In a democracy it is always shocking and disturbing when the state’s police service uses force to break up a peaceful demonstration. This is so even when the protest action is rowdy or chaotic, causes inconvenience, or disrupts the otherwise “normal” lives of others. (How normal your life can be in an obscenely unequal society like South Africa is, of course, a different question.) When members of the police service use violence against protestors where they are not legally authorized to do so – as happened several times during last week’s Fees Must Fall protest – it also signals the government’s disrespect for the dignity of those it was elected to serve.

We live in a violent society. This is not surprising as violence (or the threat of violence) was one of the main instruments through which the colonisers subjugated South Africa’s indigenous population. The apartheid government also relied heavily on state sponsored violence to enforce its rule and to remain in power. One of the reasons why patriarchy has been so resilient is that it can call upon violence and the threat of violence to assert male domination over women.

The fact that violence is deeply embedded in our society does not mean that it is either morally legitimate or legally valid for a democratic state or its institutions of higher learning to deploy the police to break up peaceful demonstrations with the use of force. To me the argument that it is permissible to employ the police to break up peaceful demonstrations by force because such peaceful protests may limit the rights of others, is not convincing.

It is for this reason that I believe the decision of the University of Cape Town early last week to obtain an interdict against protesting students (and seemingly against a Twitter hashtag) and to have that interdict enforced through brutal police action was morally indefensible.

Different rights are often in tension with one another and one right sometimes have to yield slightly to another. For example, where a large crowd gathers in front of parliament it disrupts traffic and curtails the freedom of movement of those gathered inside. Where students congregate at the entrance to a University, it may make it impossible for some students and lecturers to go about their business. Where I make use of my right to freedom of expression by criticising a politician it may diminish the dignity of that politician.

The exercise of rights by one group will often be upsetting, inconvenient or disruptive to another group. It may also limit the rights of those negatively affected by the robust exercise of the right. It is therefore unhelpful always to speak in absolutes when we talk about the enforcement or protection of rights.

Mass demonstrations are a potent weapon in the hands of people who, as individuals, have little power and are seldom listened to or heard by those in power. It is exactly because such protests cause inconvenience and disruption (and sometimes limit the rights of others) that they are noticed and may have an impact. In many instances we will have to ask whether the rights of some not to be inconvenienced or not to have their lives disrupted should take precedence over the rights of others to take part in an effective protest. In many cases the interests of one group will have to yield to the interests of another.

In some cases, most of us would not think twice before prioritising the rights of peaceful protestors above the rights of those inconvenienced by the protest. For example, not many people I know would argue that the rights of the protestors on Tahrir Square in Cairo should have yielded to the rights of the supporters of President Mubarak because the protestors caused traffic disruptions on Tahrir Square or because those protestors limited the rights of some Mubarak supporters to attend University lectures. When we are more ambivalent about the importance of the cause advanced by the protestors or where we question the moral justness of the cause, we may well object more readily to the disruption caused by the protest.

Of course, few of us would support the exercise of a right to protest when it endangers the lives of others or lead to a serious damage to property. (This is at least true for those of us who live in a democracy. In an authoritarian state, it is far more difficult to object to violent protests aimed at restoring democracy.)

I happen to think that the Fees Must Fall protest – advancing the constitutional right to higher education and the right against unfair discrimination – was morally just and that the disruptions caused to the academic programme by the peaceful protests were outweighed by the right of protestors to be heard. This is not always an easy call to make. The more drastic and prolonged the disruption and the less important the cause, the more difficult it will be to decide which right should yield.

But even if I am wrong, I would argue that it was morally wrong to use force to break up these largely peaceful demonstrations. In the absence of any real threat to person or property, any use of force to break up a protest will constitute a disproportionate response to the limitation of other rights. It is like using a hammer to try and kill a mosquito.

Where the state or an institution like a University deploys the police to use force against largely peaceful protestors, it sends a signal that the state or the institution believes it is appropriate to respond violently to those who choose to use their collective voice to be heard. This signals a callous disregard for the equal moral worth of human beings who happen to have less power than yourself.

I would argue that as long as such protests remain peaceful and as long as the they pose no immediate threat to persons or property, it is morally unconscionable to use force to break them up – no matter how inconvenient the protest may be for others. This is also in line with section 17 of the South African Constitution which guarantees for everyone “the right, peacefully and unarmed, to assemble, to demonstrate, to picket and to present petitions”.

Surprisingly, the Regulation of Gatherings Act, which was passed in the dying days of the apartheid era, at least partly gives effect to this right. The Act does not allow the police as a matter of course to use force to break up peaceful gatherings where there are no reasonable grounds to believe that the protest or demonstration threaten persons or property. Neither does the Act generally require the organisers of a demonstration or protest to ask for permission for a gathering.

The Act does require organisers to give notice of a gathering to the responsible officer. That officer is then required to negotiate in good faith with organisers in order to try an ensure that the intended gathering will not cause unnecessary disruptions to traffic and access to work. The officer can impose reasonable conditions on a gathering to ensure it remains peaceful and to prevent unnecessary disruption.

However, in terms of section 5 of the Gatherings Act a gathering can only be prohibited “when credible information on oath is brought to the attention of a responsible officer that there is a threat that a proposed gathering will result in serious disruption of vehicular or pedestrian traffic, injury to participants in the gathering or other persons, or extensive damage to property, and that the Police and the traffic officers in question will not be able to contain this threat”.

Section 7 of the Act does prohibit demonstrations near parliament unless permission is granted by the Chief Magistrate of Cape Town. Furthermore, section 12 of the Act creates a whole list of criminal offenses, including to convene a gathering without giving notice of it, carry dangerous weapons at a gathering, incite hatred or violence in respect of which no notice or no adequate notice was given, or to convene or attend a gathering that is prohibited. To convene or attend a gathering in the vicinity of parliament is therefore a criminal offense.

At least some of these potentially far-reaching prohibitions are constitutionally problematic and may impose unconstitutional limitations on the right to assemble and demonstrate guaranteed by section 17 of the Constitution.

However, regardless of whether notice was given for a gathering and regardless of whether it was illegal or not, the police are not authorised to use force to prevent members of the public to gather or to disperse a gathering unless strict requirements are complied with.

Regardless of whether permission was sought for the demonstration or not, the police would normally not be allowed to use any kind of force to disperse protestors unless reasonable grounds exist “to believe that danger to persons and property, as a result of the gathering or demonstration, cannot be averted” by other measures taken by the police. It would be allowed to use force to disperse an illegal gathering but only after stringent procedures have been followed.

Paragraph 11 of the SAPS Standing Order (General) 262 confirms this by stating that at any gathering:

“The use of force must be avoided at all costs and members deployed for the operation must display the highest degree of tolerance. The use of force and dispersal of crowds must comply with the requirements of section 9(1) and (2) of the [Gatherings] Act. During any operation ongoing negotiations must take place between officers and conveners or other leadership elements.”

However, if the negotiations and other crowd control measures do not work and there is either a threat to person or property or the gathering is illegal (in the narrow circumstances described above), the police may use the minimum force necessary to disperse the crowd but only after following the steps set out in section 9(2) of the Act and summarised in paragraph 11 of Standing Order 262 as follows:

1 Put defensive measures in place as a priority.

2 Warn participants according to the Act, of the action that will be taken against them, should defensive measures fail.

3 Bring forward the reserve or reaction section or platoon, that will be responsible for offensive measures, as a deterrent to further violence, should the above-mentioned measures not achieve the

desired result.4 Give a second warning before the commencement of the offensive measures, giving innocent bystanders the opportunity to leave the area.

5 Plan all offensive actions well and execute them under strict command after approval by the CJOC.

Even then, section 9(2) makes it clear that:

The degree of force which may be so used shall not be greater than is necessary for dispersing the persons gathered and shall be proportionate to the circumstances of the case and the object to be attained.

The Act, read with Standing Order 262, is thus unambiguous: force may only be used if it is unavoidable. The police may not use force to punish protestors for purportedly breaking the law. Protestors, like anyone else, have the right to be presumed innocent by a court until they have been proven beyond reasonable doubt to have broken the law.

Where the police use force to “punish” demonstrators for taking part in a protest for which permission was not sought or for taking part in an illegal protest, the police are taking the law into their own hands and are acting unlawfully. In principle there is little difference between a police officer using force to disperse protestors where there is no threat to person or property and where it was unavoidable, and a group of vigilantes assaulting a person suspected of stealing a loaf of bread.

In any event, if it is impossible to avoid and the use of force is required, the police are bound by Standing Order 262 which imposes the following requirements on them:

(a) the purpose of offensive actions are to de-escalate conflict with the minimum force to accomplish the goal and therefor the success of the actions will be measured by the results of the operation in terms of cost, damage to property, injuries to people and loss of life;

(b) the degree of force must be proportional to the seriousness of the situation and the threat posed in terms of situational appropriateness;

(c) it must be reasonable in the circumstances;

(d) the minimum force must be used to accomplish the goal; and

(e) the use of force must be discontinued once the objective has been achieved.

In several instances last week, the police failed to negotiate with demonstrators, failed to make every effort to avoid conflict, failed to give one, let alone two warnings to protestors to disperse before using force, and failed to use the minimum force required to protect property and persons.

Of course, as the Farlam Commission Report made clear, this failure of the police to comply with the law is the rule rather than the exception. It led to the killing of 34 miners at Marikana. It also led to the killing of Andries Tatane and many others. It speaks to the fact that the institutional culture within the police service has not been effectively transformed since the end of apartheid.

While the Fees Must Fall campaign has raised critical questions about the policy choices of our government and of university managements regarding the allocation of funding, it has also raised questions about its willingness to use state violence to defend its policy choices and to protect its interests – even against peaceful protestors. These questions are worth asking. It is also important for those inside and outside academia to continue asking such critical questions and to demand answers from those in authority.

BACK TO TOP