Quote of the week

[T]he moral point of the matter is never reached by calling what happened by the name of ‘genocide’ or by counting the many millions of victims: extermination of whole peoples had happened before in antiquity, as well as in modern colonization. It is reached only when we realize this happened within the frame of a legal order and that the cornerstone of this ‘new law’ consisted of the command ‘Thou shall kill,’ not thy enemy but innocent people who were not even potentially dangerous, and not for any reason of necessity but, on the contrary, even against all military and other utilitarian calculations. … And these deeds were not committed by outlaws, monsters, or raving sadists, but by the most respected members of respectable society.

Eichmann in Jerusalem: A Report on The Banality of Evil

No, religious freedom does not justify discrimination

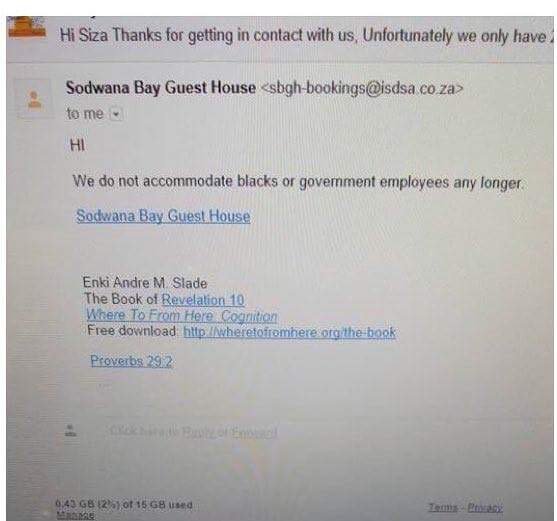

Another week. Another incident of racial and homophobic discrimination comes to light. This time the perpetrator is the owner of Sodwana Bay guesthouse, André Slade, who says no black people or gays and lesbians are welcome at his establishment. Slade is obviously a bit unhinged and his views would be considered extreme – even by middle of the road racists and homophobes. But many share his unfounded belief that the religious views of the owner of a private business justifies discrimination.

For some reason that defies logic, many South Africans still believe the myth that their right to freedom of association, their right to property, or their right to freedom of religion allows them to discriminate against others on the basis of race, sex or sexual orientation.

This myth – repeated over and over by the defenders of discrimination as if it is a magic spell aimed at warding off witches and evils spirits – is based on the belief that early twentieth century legal arrangements in colonial Britain still apply in South Africa. Those who perpetuate this myth are profoundly ignorant about South African law.

It is tedious to have to keep on debunking this myth – like having to tell your drunk uncle every year at Christmas lunch that the World Trade Centre did in fact collapse and that it was not all a special effects video concocted by the CIA.

There are at least two reasons why some people still peddle the myth that their freedom of religion or association trumps the rights of others not to be discriminated against. First, not enough South Africans challenge this type of discrimination in the Equality Court. Second, the fines imposed by Equality Courts are too low to put some of these establishments out of business.

It is only when their livelihoods are threatened that the owners of private businesses will stop believing in the myth that private discrimination is protected by the Constitution.

Let’s start with the text of the Constitution itself.

Section 9(4) of the Bill of Rights clearly states:

No person may unfairly discriminate directly or indirectly against anyone on one or more grounds in terms of subsection (3). National legislation must be enacted to prevent or prohibit unfair discrimination.

The “person” referred to in section 9(4) includes both individual people and private businesses. The grounds listed in subsection (3) includes race, gender, sex, pregnancy, marital status, ethnic or social origin, colour, sexual orientation, age, disability, religion, conscience, belief, culture, language and birth.

In a long line of judgments, the Constitutional Court held that the provisions of the Constitution must be interpreted in the light of South Africa’s history of racial oppression and that one of the major aims of the Constitution is to dismantle patterns of discrimination, disadvantage and harm associated with racism, sexism, and homophobia.

Given this jurisprudence of the Constitutional Court relating to the importance of the right to equality in our constitutional framework, it is hard to imagine that it will ever find that the right of a private business owner to freedom of religion, to property rights or to freedom of association will trump the right of clients not to be discriminated against contained in section 9(4).

To give effect to this prohibition on discrimination by individuals and private businesses, Parliament in 2000 adopted the Promotion of Equality and Prevention of Unfair Discrimination Act (PEPUDA).

Section 5 of the PEPUDA states that its provisions bind “the State and all persons”. It also states that if “any conflict relating to a matter dealt with in this Act arises between this Act and the provisions of any other law… the provisions of this Act must prevail.”

This means that PEPUDA trumps the common law, customary law and any other legal provisions that may (in the absence of PEPUDA) have protected the property rights, and the rights to freedom of association and to freedom of religion of private business owners.

This provision is in line with the requirement contained in article 2(d) of the International Convention on the Elimination of All forms of Racial Discrimination which requires each state that signed and ratified this international treaty to “prohibit and bring to an end, by all appropriate means, including legislation as required by circumstances, racial discrimination by any persons, group or organisation.”

Even in a country like England – with no written Constitution and a less vibrant human rights regime than South Africa – its Supreme Court ruled in 2013 that the English law prohibited the Christian owners of a guest house from discriminating against a gay couple.

Section 6 of the PEPUDA prohibits both the State and any person from unfairly discriminating against any other person. Because the Act prohibits “unfair discrimination” some distinctions between people are justified. Section 14 contains a long list of factors to be considered when deciding whether discrimination is unfair.

One of the most important factors to be considered is “the position of the complainant in society and whether he or she suffers from patterns of disadvantage or belongs to a group that suffers from such patterns of disadvantage”.

This factor is important because it recognises that discrimination predominantly occurs when members of a socially or economically powerful group treats members of a socially or economically vulnerable group in a manner that perpetuates stereotypes or subjugates or oppresses the marginalised group.

Those who belong to a group with the power to subjugate others who are different from them (rich people, white people; men; heterosexuals) are far more likely to be found to have unfairly discriminated against somebody than those who tend not to have such power (poor people, black people, women, gays and lesbians).

This is why lawyers who establish a White Lawyers Association (WLA) will almost certainly be acting in breach of PEPUDA while the Black Lawyers Association (BLA) is almost certainly compliant with PEPUDA. Because white lawyers have not systematically been discriminated against over the past 400 years and because they are not systematically subjected to discrimination, they would merely be protecting their unearned privilege if they formed a WLA and would be perpetuating discrimination. The opposite is true for the BLA.

Section 14 also requires a court to ask whether the discrimination is systemic in nature and whether and to what extent the person being accused of discrimination has taken reasonable steps “to address the disadvantage which arises from or is related to one or more of the prohibited grounds”. In other words, PEPUDA permits a private institution to enforce redress measures (also called affirmative action measures) to address the effects of past and ongoing discrimination.

In fact, the Constitutional Court suggested in Minister of Finance v Van Heerden that the Constitution requires the state and private institutions in certain circumstances to implement redress measures to eradicate the deeply embedded patterns of disadvantage and harm which resulted from colonialism, apartheid, and hetero-patriarchy.

A private individual may stand a chance to convince a court that the discrimination is not unfair if he or she could show that there was a legitimate purpose for the discrimination or that the discrimination reasonably and justifiably differentiates between persons according to objectively determinable criteria, intrinsic to the activity concerned.

For example, where a film company hired a white male actor to play Eugene Terreblanche in a movie about neo-Nazi’s, it would be difficult to convince the court that this constituted unfair discrimination based on race, sex or gender as it is intrinsic to the job that Terreblanche should be played by a white man.

But in Hoffmann v South African Airways the Constitutional Court cautioned that:

Prejudice can never justify unfair discrimination. This country has recently emerged from institutionalised prejudice. Our law reports are replete with cases in which prejudice was taken into consideration in denying the rights that we now take for granted. Our constitutional democracy has ushered in a new era – it is an era characterised by respect for human dignity for all human beings. In this era, prejudice and stereotyping have no place.

This means that prejudice – even prejudice informed by genuinely held religious beliefs – cannot justify discrimination. Enforcing or protecting a prejudice could therefore never be a legitimate purpose for unfairly discriminating against someone based on their race, sex, gender or sexual orientation.

A defendant in a discrimination case would therefore not be able to claim that his or her religious views which holds that some people are not fully human because of their race or sex or sexual orientation (obviously a kind of prejudice) justifies his or her discrimination.

Similarly, a person would never be able to convince a court that he or she has the right to associate only with white people or heterosexuals because that is just a prejudice the person has. As the choice of association is based on prejudice, it could never trump the right not to be unfairly discriminated against.

In terms of section 21 of PEPUDA the Equality Court has a very broad discretion when deciding what remedies to impose on the discriminating party.

It can order the private business or person to stop discriminating, to change its policies, to offer an apology, or to order the payment of damages in the form of an award to an appropriate body or organisation. It can also make an appropriate order of a deterrent nature, including the recommendation to the appropriate authority, to suspend or revoke the licence of a person.

This means that PEPUDA has real teeth and allows a court to impose drastic sanctions against individuals or private businesses who discriminate against individuals based on their race, sex, gender or sexual orientation.

The vigorous enforcement of PEPUDA will, of course, not stop all people from harbouring racist, sexist or homophobic views. In any event, the problem of racism, sexism and homophobia is about more than the personal attitudes of individuals. The very way in which society is structured promote the well-being of dominant groups to the detriment of subordinated groups and these arrangements are difficult to change overnight.

However, if more people used the Equality Courts to challenge discrimination and if Equality Courts imposed heavier penalties on private individuals and businesses who unfairly discriminate, it might at least help to shatter the bizarrely resilient myth that the right to freedom of association, their property rights, or their right to freedom of religion allows private individuals or businesses to discriminate against others on the basis of race, sex, gender or sexual orientation.

For example, if somebody were to approach the Equality Court with a request to rule that Sodwana Bay guesthouse and its owner André Slade unfairly discriminated against black people and against gays and lesbians, the Court would be able to impose an award of R500 000 damages on the guesthouse or on Mr Slade personally.

Such a harsh penalty may make other owners of private businesses sit up and take notice. They may not stop harbouring racist, sexist or homophobic views. But some of them may at least start to comply with the law.

BACK TO TOP