Quote of the week

[T]he moral point of the matter is never reached by calling what happened by the name of ‘genocide’ or by counting the many millions of victims: extermination of whole peoples had happened before in antiquity, as well as in modern colonization. It is reached only when we realize this happened within the frame of a legal order and that the cornerstone of this ‘new law’ consisted of the command ‘Thou shall kill,’ not thy enemy but innocent people who were not even potentially dangerous, and not for any reason of necessity but, on the contrary, even against all military and other utilitarian calculations. … And these deeds were not committed by outlaws, monsters, or raving sadists, but by the most respected members of respectable society.

Eichmann in Jerusalem: A Report on The Banality of Evil

Why is Film and Publications Board ignoring Constitutional Court judgment?

Ignoring the Constitutional jurisprudence on the classification of “child pornography” (which it is bound by), as well as the decisions of the Film and Publications Review Board (which ought to guide its work) classifiers at the Film and Publications Board (FPB) last week wrongly banned a movie which would have been shown at the Durban Film Festival, either because they are ignorant of the law in terms of which they must exercise their powers, or because they decided to be guided by a misplaced, conservative, moralistic fervour – instead than by the law that they are bound by.

Last year I was asked to assist the FPB with the training of its classifiers. One of the “trainers” brought in for the workshop was a fire and brimstone preacher, ranting and raving about the “sins” of homosexuality and about the general “sexual depravity” of sex out of wedlock. Unlike the new head of the Vatican bank, who was allegedly caught stuck in an elevator with a rent boy (we are not told if they were going up or down), the fire and brimstone preacher did not display a healthy attitude towards sexual pleasure.

It was standard stuff for a man who makes a living out of scaring susceptible people into giving him money while instilling fear and shame into them for having a healthy and unremarkable attitude towards sex. But his hate-filled sermon was completely out of place at a workshop aimed at training classifiers to interpret and apply the provisions of the Film and Publications Act within the parameters of South Africa’s constitutional freedom of expression jurisprudence.

It was standard stuff for a man who makes a living out of scaring susceptible people into giving him money while instilling fear and shame into them for having a healthy and unremarkable attitude towards sex. But his hate-filled sermon was completely out of place at a workshop aimed at training classifiers to interpret and apply the provisions of the Film and Publications Act within the parameters of South Africa’s constitutional freedom of expression jurisprudence.

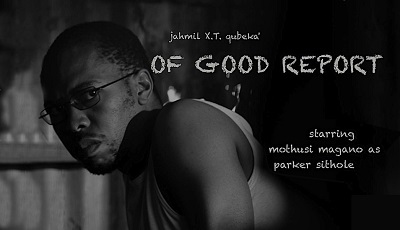

I was therefore not surprised to read that classifiers of the FPB last week banned the movie Of Good Report, by the Eastern Cape director Jahmil XT Qubeka, on the grounds that it contained “child pornography”, thus preventing it from being shown at the opening of the Durban Film Fesitval. The movie, which apparently makes a strong statement against the practice of school teachers acting as sugar daddies (I cannot know, because at the time of writing it would be a criminal offence to posses, let alone watch, the movie), contains a simulated oral sex scene between two actors who remain fully clothed, one of whom is portrayed as being younger than 18.

Section 18(3) of the Film and Publications Act requires the FPB to ban any movie that contains “child pornography”. Once a movie has been banned, it is a criminal offense to possess a copy of it and you are required to destroy all copies of the film in your possession or face criminal conviction (subject to an appeal to the Publications Review Board).

You do not have to be a legal expert to know that the movie was almost certainly wrongly classified as “child pornography”. The Act defines “child pornography” as including any image or any description of a person who is or who is depicted as being under the age of 18 engaged in “sexual conduct”. Sexual conduct is broadly defined and includes even the indirect fondling of breasts.

But despite these definitions the Act does not specifically define what would constitute “pornography” (as opposed to “child pornography”). Most of us would know that pornography is notoriously difficult to define. What, for example, is the difference between pornography and works of eroticism?

In a now famous (but brief) concurring judgment handed down in 1963, Mr Justice Potter Stewart of the US Supreme Court (in the case of Jacobellis v. Ohio) stated that hard-core pornography was very difficult to define “and perhaps I could never succeed in intelligibly doing so. But,” he added, “I know it when I see it”.

The classifiers at the FPB also thought they knew child pornography when they saw it. Unfortunately they ignored the Constitutional Court judgment on the meaning of the definition of “child pornography” in the Act, set out in the case of De Reuck v Director of Public Prosecutions (Witwatersrand Local Division) and Others. They also ignored the Film and Publications Review Board decision in which it overturned the banning imposed on the Argentinian movie XXY¸ which relied heavily on the Constitutional Court judgment.

In the De Reuck case the Court concluded that the primary meaning of “child pornography” in the Act related to the question of whether the film (or other publication) could objectively be deemed to appeal to the erotic as opposed to the aesthetic. As such a film or publication could only be classified as “child pornography” if it primarily involved the stimulation of erotic feelings rather than aesthetic feelings. The Court (in a judgment authored by Deputy Chief Justice Langa) then continued:

I would observe, however, that erotic and aesthetic feelings are not mutually exclusive. Some forms of pornography may contain an aesthetic element. Where, however, the aesthetic element is predominant, the image will not constitute pornography. With this qualification, the dictionary definition above fairly represents the primary meaning of ‘pornography’. ‘Child pornography’ bears a corresponding primary meaning where the sexual activity described or exhibited involves children. In my view, the section 1 definition is narrower that this primary meaning of child pornography.

As is always the case with any meaningful analysis of works of artistic expression, the context is all important. Unfortunately the members of the moral thought police who decided to ban Of Good Report because they deemed it to be “child pornography” clearly did not take the context into account.

As the De Reuck judgment made clear, it is not possible to determine whether an image as a whole amounts to child pornography without regard to the context. When you decide to classify a 90 minute film as child pornography after only watching 29 minutes – as the classifiers at the FPB did – you have wrongly failed to take account of the context and the artistic merit of the film. As the Constitutional Court pointed out:

It is probable that other parts of the film or publication alleged to contain child pornography may indicate whether the predominant purpose of the material, objectively construed, is to stimulate sexual arousal amongst its target viewers. The Act should be interpreted to allow consideration of such contextual evidence when it is relevant since the statute does not, in my view, preclude it.

It is true that the definition of “child pornography” had been amended in 2004 and that the De Reuck judgment dealt with the old definition. But as the decision of the Film and Publication Review Board found when it overturned the banning on the Argentinian movie XXY, the change in the definition was simply to clarify and simplify an unnecessarily wordy subsection and did not render the reasoning in De Reuck inapplicable.

In the case of XXY the FPB first banned the movie for containing child pornography as it depicted simulated sex between two actors presented as being younger than 18. The Review Board overturned that decision – relying on the Constitutional Court judgment in De Reuck – pointing out that the movie carried the profound and important message that premature decisions made at the birth of an intersex child can have seriously prejudicial and agonisingly tragic consequences for the child as s/he matures. Summarising the De Reuck interpretation of the Act the Review Board said:

The overarching enquiry, objectively viewed, is whether the purpose of the image is to stimulate sexual arousal in the target audience. This entails considering the context of the publication or film in which the image occurs as a visual presentation or scene. The court conducts the enquiry from the perspective of the reasonable viewer.

Although I am at present not allowed to see Of Good Report and have not seen it, the fact that everyone agrees that the offending scene contains no explicit sexual depictions; that the movie was chosen to open the Durban Film Festival and must be of some artistic value; that the FPB classifiers only watched 29 minutes of the movie before banning it; and that (given its important overall message) it would be difficult if not impossible for a reasonable person (judging objectively) to conclude that the main purpose of the movie was to “stimulate sexual arousal” in the target audience (those who hang out at film festivals); the decision by the classifiers of the FPB seem to make no sense.

Of course, I do not wish to give the prurient classifiers at the FPB – who seem to see perversion in any (simulated) sexual encounter involving an actor depicted younger as 18 – any ideas. But how long before they exercise their acute “artistic judgment” over a classic novel such as Vladimir Nabokov’s Lolita, and ban the book as containing child pornography? It might be a widely studied classic literary text, but if you apply the strict criteria the FPB applied to Of Good Report (in contrast to its own Review Board and the Constitutional Court) I have no doubt they would have to ban a work of literature by one of the greatest novelists of the twentieth century.

However, if they were to familiarise themselves with the relevant Constitutional Court judgments as well as the decisions of their own Review Board, they would have to stop banning films without even taking into account either the context or the artistic merit of the movie. But it is, of course, an open question whether most classifiers working for the FPB are capable of identifying artistic merit in a creative work of fiction.

BACK TO TOP