Quote of the week

[T]he moral point of the matter is never reached by calling what happened by the name of ‘genocide’ or by counting the many millions of victims: extermination of whole peoples had happened before in antiquity, as well as in modern colonization. It is reached only when we realize this happened within the frame of a legal order and that the cornerstone of this ‘new law’ consisted of the command ‘Thou shall kill,’ not thy enemy but innocent people who were not even potentially dangerous, and not for any reason of necessity but, on the contrary, even against all military and other utilitarian calculations. … And these deeds were not committed by outlaws, monsters, or raving sadists, but by the most respected members of respectable society.

Eichmann in Jerusalem: A Report on The Banality of Evil

Zanna Bliss – Made in China for the World Cup

Made In China for the World Cup

By Zanna Bliss

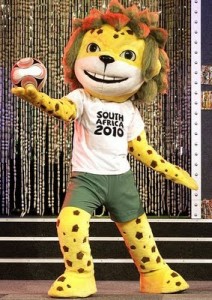

Last week, while walking down Cape Town’s Main Road in the Woodstock/Salt River area where I live, I saw something I had never seen before. At one of the closed-down, decrepit, art deco-era textile factories, a door was standing ajar. Curious, I peered inside, and upon looking in, saw dozens of happy textile workers making tee-shirts for the upcoming soccer extravaganza featuring Zakumi, the official mascot for the 2010 FIFA World Cup.

Just kidding… what I saw was surprising, even though I should have known what to expect: a large, airy room, empty but for the weeds growing through the cracks in the concrete floor and the rays of sunlight streaming through broken windows.

On Friday, the Congress of South African Trade Unions (COSATU) conducted a protest demonstration outside FIFA’s Cape Town office, objecting to the outsourcing of manufactured Zakumi products, including jerseys, scarves, dolls and the mascot itself, to foreign companies. Ordinarily, I am sympathetic to COSATU’s initiatives, as it mostly appears that they are genuinely trying to advance the interests of South Africa’s working class.

I worry though that their demands, while legitimate, are too grand, too unrealistic, to fit with the current economic realities that face our nation. ‘Good ol’ COSATU,’ I’ll say to myself, ‘they sure do know how to deliver a memorandum.’ In this case though, they might actually have a very valid point.

Zakumi is no stranger to controversy. Senior ANC MP Shiaan-Bin Huang was given the contract for manufacturing the mascot, a job he allegedly outsourced to a factory in China. It has since come to light that the Chinese factory workers tasked with assembling Zakumi dolls are paid the equivalent of R23 each work day (which may be as long as 13 hours), and are subjected to sub-standard working conditions. On 3 February, COSATU warned FIFA that it would not allow Zakumi to be sold in South Africa, pointing out that South African industry is more than capable of being tasked with manufacturing the mascot.

In President Zuma’s State of the Union address last week, he spoke of the need to build an economy that creates jobs instead of depriving them from South Africans, and of the imperative of continued economic growth that would give rise to more employment opportunities. While the upcoming World Cup does provide job opportunities, many of these are guaranteed to be short-lived.

The symbolism of manufacturing the official mascot for the first-ever African world cup on African soil and by African hands is not unimportant, but it would be more prudent for policy makers and economic planners – whomever they may be – to concentrate on long-term strategies for sustainable and self-replicating job opportunities. In a country where conservative figures place unemployment between 20 – 25% of the workforce, we need to look beyond 2010, with all its glitz and Zakumi-glamour, to a future in which workers are protected and the unemployed are afforded the opportunity to work, thereby giving more substance to the right to human dignity and the right to choose one’s trade, occupation or profession, as enshrined in our Constitution’s Bill of Rights.

At Friday’s demonstration, COSATU representatives, true to form, submitted a memorandum to the World Cup Local Organising Committee, expressing dissatisfaction with the outsourced manufacture of Zakumi mascots and apparel. The protesters, including aggrieved traders and textile workers, emphasised their support for the World Cup, while lamenting the fact that taxpayer’s money is being used to cover the costs of the event without being fed back into employment opportunities for locals. They stated that while they knocked on FIFA’s door on that occasion, next time they would be prepared to kick it down.

The South African government and those tasked with organising the World Cup need to seriously consider these valid grievances, as they are symptomatic of issues that are sure to remain on our political landscape until such time as they are dealt with effectively. What is more, our government should start looking beyond the ephemeral opportunities provided by the FIFA World Cup for ways to open doors to real and lasting employment for our people.

Standing up to the global economic goliath that is China is going to be difficult – as illustrated by US President Obama’s last-minute cancellation of his meeting with the Dalai Lama this last week – but it is going to have to happen if we are serious about advancing human rights and job creation in South Africa. Instead of supporting Chinese industry with its shady conception of human and workers’ rights, our government could utilise existing infrastructure and build an expanded public works programme, thereby creating more job opportunities for South African workers and reinforcing its oft-stated commitment to human rights and poverty alleviation.

- Zanna Bliss is a UCT Law student.