Quote of the week

[T]he moral point of the matter is never reached by calling what happened by the name of ‘genocide’ or by counting the many millions of victims: extermination of whole peoples had happened before in antiquity, as well as in modern colonization. It is reached only when we realize this happened within the frame of a legal order and that the cornerstone of this ‘new law’ consisted of the command ‘Thou shall kill,’ not thy enemy but innocent people who were not even potentially dangerous, and not for any reason of necessity but, on the contrary, even against all military and other utilitarian calculations. … And these deeds were not committed by outlaws, monsters, or raving sadists, but by the most respected members of respectable society.

Eichmann in Jerusalem: A Report on The Banality of Evil

Keep your neighbours happy

Running an illegal shebeen can be a hazardous affair. The owners of the shebeen run the risk of losing their family home (from which they run the illegal shebeen), especially if they have a neighbour who would not let matters rest and is so incensed about the evil effects of the shebeen that he is prepared to write more than 50 letters of complaint to various government departments in an attempt to bring an end to the unlawful selling of liquor from the property. Better to run an illegal shebeen where the neighbours are less civic minded or where people are so poor that the politicians and police will happily ignore their complaints about the shebeen (unless an election is around the corner, of course).

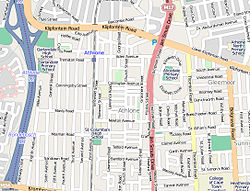

This is what happened to the Van der Burgs from Athlone, a suburb relatively close to the centre of Cape Town.  The High Court had ordered that their house (from which they operated the bothersome illegal shebeen) be forfeited to the state in terms of the provisions of the Prevention of Organised Crime Act (POCA). They challenged this order in the Constitutional Court, but yesterday a unanimous Court (in a judgment written by Van der Westhuizen J) confirmed the High Court order in the judgement of Van der Burg and Another v National Director of Public Prosecutions and Another.

The High Court had ordered that their house (from which they operated the bothersome illegal shebeen) be forfeited to the state in terms of the provisions of the Prevention of Organised Crime Act (POCA). They challenged this order in the Constitutional Court, but yesterday a unanimous Court (in a judgment written by Van der Westhuizen J) confirmed the High Court order in the judgement of Van der Burg and Another v National Director of Public Prosecutions and Another.

The Van der Burgs are a married couple with four children, three of whom are minors. The market value of their house at the time of the forfeiture in 2006 was approximately R350 000.00. For many years they had been illegally running a shebeen from their house, which is about 30 meters from the St. Raphael’s Primary School.

They approached the Constitutional Court, arguing, first, that POCA does not apply to the running of a shebeen and, second, that the forfeiture of their house was in any case a disproportionate step that infringed on their right to property guaranteed in the Constitution. POCA, they argued, allows a court to order the forfeiture of property that are “instrumental” in the commissioning of organised crime. Running an illegal shebeen can be said to be many things, but it is not usually associated with organised crime.

The Constitutional Court rejected the first argument, pointing out that POCA allows a court to order the forfeiture of a property “which is concerned in the commission or suspected commission of an offence”, including “any offence the punishment wherefore may be a period of imprisonment exceeding one year without the option of a fine”. The offence in this case, which has repeatedly resulted in police action (all those letters by the neighbour obviously having the desired effect), is the selling of liquor without a license, criminalised by the Liquor Act which allows for the imposition of a fine or to imprisonment for a period of not more than five years.

Regarding the second argument the Court recognised that the Constitution protects the right not to be arbitrarily deprived of one’s property. But there is only an arbitrary deprivation if the forfeiture is not proportionate. The Court looked at three issues in dealing with this proportionality enquiry.

First, it found that in this case the forfeiture provisions “were not used whimsically (or as a ‘top up’)” to punish the Van der Burgs for activities criminal activities that could otherwise be dealt with by the criminal law.

The evidence of all the arrests, admissions of guilt, seizures of liquor and preservation order do not show a failure to employ ordinary criminal law instruments, but rather that the continuation of the criminal conduct was more profitable, even with the sanctions imposed, than ceasing to engage in criminal conduct. In other words, “crime pays”. The forfeiture was sought as a last resort to put an end to the criminality by removing the main instrument used in its commission. This is not an abuse of POCA or the criminal justice system and does not offend the Constitution.

Second, the Court weighed the seriousness of forfeiture against the seriousness of selling liquor without a licence, finding that the “patent and on-going harm caused by the” running of the shebeen required alternative measures, over and above those available in the ordinary criminal law. Even if harsh, this was necessary to bring the unlawful activity to an end. Because there was a close relationship between the illegal activity and the property forfeited, a property used for more than six years in running an illegal shebeen, the seriousness of the on-going crime outweighed the seriousness of depriving the Van der Burgs of their property.

The applicants conduct their illegal activity with barefaced disregard for the law. In fact, the applicants’ counsel contended on their behalf that the forfeiture would be pointless since they would simply re-open their shebeen elsewhere. The countless difficulties that the police have experienced in stopping their criminal conduct seem to give them impetus to persist. Their use of “runners” to carry out the illegal activity from the property on their behalf indicates the extent to which the conduct is part of a co-ordinated business to profit from criminal activity. This is precisely what POCA targets.

Third, the court had to ask what was the relevance of the possible homelessness of the Van der Burgs and their children and of section 26 of the Constitution (which guarantees the right of access to housing), as well as legislation prohibiting illegal evictions, on the proportionality enquiry. The Court had little sympathy for the argument put forward by the Van der Burgs that the forfeiture would leave them and their children homeless, stating that the “bald allegation of homelessness does not seem to be borne out by the facts”. The Van der Burgs had not shown that their monthly income is insufficient to lease another home while supporting their children. And as Van der Westhuizen remarks, rather whimsically: “In any event, the possibility of losing a home is certainly a consequence worth considering when one persistently uses it for a criminal business venture”.

The amicus curia had further contended – based on section 28(2) of the Constitution which guarantees the rights of children – that the forfeiture should not be granted until and unless a curator ad litem has been appointed to represent the children’s interests. This argument was also met with little sympathy by the Court. It is true that “[a] child’s best interests are of paramount importance in every matter concerning the child” and that the interests of the children are a separate and important consideration and cannot merely be dealt with as one of several factors weighed on the proportionality scale. In particular cases the interests of the children may require steps to be taken independently of the conclusion reached on forfeiture at the end of the proportionality enquiry.

However, in this case the High Court gave due consideration to the question whether the forfeiture would result in the family becoming homeless. The court was satisfied that the Van der Burgs and their children would not be left destitute. There was therefore no immediate concern that the interests of the children would not be taken care of.

This judgment illustrates the potentially far-reaching effects of the Prevention of Organised Crime Act, whose tentacles can reach far beyond the traditional criminal activities associated with organised crime. It also illustrates that the Constitutional Court is perhaps less sympathetic to those who consistently flout the law (to the detriment of the larger community), than is often believed. Lastly, it illustrates that one should usually try not to alienate one’s neighbours, especially if those neighbours are civic minded and become so incensed by one’s criminal activity that they are prepared to write more than 50 letters to various authorities in an attempt to get them to take their complaints against your activities seriously.

BACK TO TOP