Quote of the week

[T]he moral point of the matter is never reached by calling what happened by the name of ‘genocide’ or by counting the many millions of victims: extermination of whole peoples had happened before in antiquity, as well as in modern colonization. It is reached only when we realize this happened within the frame of a legal order and that the cornerstone of this ‘new law’ consisted of the command ‘Thou shall kill,’ not thy enemy but innocent people who were not even potentially dangerous, and not for any reason of necessity but, on the contrary, even against all military and other utilitarian calculations. … And these deeds were not committed by outlaws, monsters, or raving sadists, but by the most respected members of respectable society.

Eichmann in Jerusalem: A Report on The Banality of Evil

Murder in the wild North West

When Moss Phakoe, the late ANC councillor in the Rustenburg municipality, was murdered for blowing the whistle on alleged corruption in the Rustenburg Local Municipality in North West, there was every reason to believe that his murderers would never be brought to book. After all, the main suspects were the then ANC mayor, Matthew Wolmarans, and his bodyguard, Enoch Matshaba. Wolmarans was politically well-connected in the ANC and exposing his involvement in corruption and murder would embarrass the party and would not be politically expedient for party power-brokers.

Fortunately for South Africa – but unfortunately for Wolmarans and Matshaba – Phakoe’s friend Alfred Motsi, a fellow councillor and Cosatu member, relentlessly pursued the matter (with the assistance of Cosatu head office), forcing the authorities to act, despite severe reluctance to do so. This finally led to the conviction of Wolmarans and Matshaba for Phakoe’s murder last week. They had killed him to cover up the corruption in the municipality and to protect the financial interests of the politically well-connected network of ANC loyalists and tenderpreneurs in the area.

The story of the murder of Moss Phakoe (and what looks like the subsequent attempted cover-up) provides a rather stark and depressing picture of the state of local government in South Africa. The fact that some local municipalities have sunk into a cesspit of corruption, nepotism and naked power-politics, is also reflected by the harsh, incontrovertable, facts and figures produced by the Auditor General. This week, Auditor General Terence Nombembe announced that there were no fewer than 64 municipalities (23% of the total) with adverse opinions or disclaimers against them, and a further 37 just didn’t submit their statements in time. The table below summarises the picture:

As Paul Berkowitz noted in the Daily Maverick (from which I borrowed these tables) in the Eastern Cape, Free State, Limpopo, Northern Cape and the North-West more than half of the municipalities are bad-news stories. In the Free State, for example, a municipality is more likely to have an adverse opinion or disclaimer than not. In the North-West – the province where Phakoe lived and died – over 60% of all municipalities didn’t submit their financial documentation to the auditor-general’s office on time.

As Paul Berkowitz noted in the Daily Maverick (from which I borrowed these tables) in the Eastern Cape, Free State, Limpopo, Northern Cape and the North-West more than half of the municipalities are bad-news stories. In the Free State, for example, a municipality is more likely to have an adverse opinion or disclaimer than not. In the North-West – the province where Phakoe lived and died – over 60% of all municipalities didn’t submit their financial documentation to the auditor-general’s office on time.

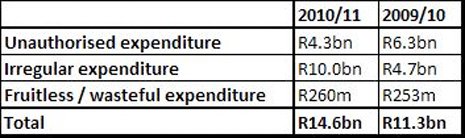

The figures for unauthorised, irregular, fruitless and wasteful expenditure also appear to be getting worse:

As the Auditor General admitted, one of the biggest problems with the failing Municipalities is that those responsible for the mess are seldom held accountable – either politically, in terms of the labour law or in terms of criminal sanction. Neither are those involved in unauthorised, irregular or wasteful expenditure held to account.

As the Auditor General admitted, one of the biggest problems with the failing Municipalities is that those responsible for the mess are seldom held accountable – either politically, in terms of the labour law or in terms of criminal sanction. Neither are those involved in unauthorised, irregular or wasteful expenditure held to account.

It does not help matters that the criminal justice system, along with the South African Police Service and Intelligence Services, have systematically been politicised and captured by whoever is the ruling faction inside the governing party, culminating in the shameless and self-serving appointment by President Jacob Zuma of the dishonest Menzi Simelane as National Director of Public Prosecutions and the incompetent and possibly corrupt (if Judge Jake Moloi is to be believed) Bheki Cele as Police Commissioner.

When Chief Financial Officers and Mayors across South Africa believe that as long as they have political support, they will be protected by their party and its leadership and will be able to avoid both political accountability as well as criminal sanction, a culture of impunity will thrive and nepotism, fraud and corruption will flourish like an agressive form of cancer, eventually killing the patient.

As Alfred Motsi tells it, in some parts of South Africa, the cancer may already have spread and the patient may be terminal (and may as well be released on medical parole). Motsi believes that Phakoe died because ANC leaders were not prepared to act against Wolmarans and his cronies and he is not afraid to say so.

Motsi told a newspaper that he and Phakoe had meetings with ANC structures in the province, “went to individual ANC bigwigs, including to Gwede Mantashe, senior party leaders Siphiwe Nyanda and Billy Masetlha, among others” to get them to take action “but no action was ever taken”. In the end, the two met with President Jacob Zuma at Nkandla late in December 2008 to raise the issue of the corrupt Wolmarans.

Motsi said after a chat with Zuma, Mantashe invited him and Phakoe to a meeting on January 8, 2009, in Potchefstroom, where the ANC’s top six were present, as well as Wolmarans and the provincial leadership. Mantashe denied this, saying Zuma never discussed any Rustenburg corruption allegations with him, but admits that “some people” went to Nkandla. Motsi, on the other hand, claims he was scorned by Mantashe as a “troublemaker” and that the organisation’s top national leadership did little to stop an apparently untouchable Wolmarans. Mantashe rejected Motsi’s claims, but admitted that he had spoken several times to him prior to the murder. He said Motsi had been “rude” and unrealistic in his demands.

One wonders what these “unrealistic demands” might have been. Maybe they included the demand that ANC leaders should take the allegations of corruption against Wolmarans – backed up by evidence – seriously, that the leadership had to deal with Wolmarans politically and that it had to take steps to ensure that the SAPS properly investigate the allegations against Wolmarans.

Mantashe has not said why he found Motsi’s demands “unrealistic”, but in the aftermath of the murder and Wolmarans’ conviction, his admission seems quite damning to me. It seems to point to the major problem faced by the ANC: by viewing members as part of a large family or akin to a close-knit ethnic tribe, there is a grave danger that loyalty to the party is viewed as more important than rooting out corruption or obeying the law and – god forbid – than pursuing justice on behalf of the people.

If you happen to be inside the family (and as long as you do not threaten the President’s political ambitions or have not fallen out with the wrong faction), the family will nurture you and look after you and will protect you from being held politically or criminally accountable for your venal and crimninal acts. The fact that despite allegations of corruption having been made against him, Wolmarans was not removed from council but was moved to the position of speaker in the municipality illustrates this point rather well.

And then some people still wonder why corruption and maladministration is such a huge problem in South Africa. In the absence of both political accountability and the threat of criminal sanction, backed up by honest, diligent, and depoliticised investigations by the police and unbiased and non-political decisions by the NPA on who to prosecute and who not to prosecute, the amount in unauthorised, irregular and wasteful expenditure wasted by municipalities will increase exponentially, inevitably leading to the complete collapse of local government in the worse affected areas.

This is why it is so worrying, as Zwelinzima Vavi recently pointed out in an article in City Press, that everything possible was done to delay the police investigation, protect the culprits and keep the truth about the killing of Moss Phakoe from the people. If it was not for Cosatu and the efforts of Motsi, Wolmarans might well have been on his way to a more important leadership position in the ANC.

According to Motsi, the late Sicelo Shiceka, was asked by the ANC leaders to investigate the allegations of corruption in the Rustenburg municipality. “A dossier including more evidence was compiled by myself and Phakoe which was handed to Shiceka in a meeting on March 12. Wolmarans was present and I testified in court during the murder trial how Wolmarans’ face had immediately changed when Phakoe told Shiceka evidence on the dodgy Rustenburg Kloof (a council-owned resort which had its running outsourced through tender process) deal,” Motsi said. According to evidence led in court, Phakoe told the mayor: “Hurt me, but don’t kill me.” Two days later, Matshaba shot Phakoe as Phakoe was parking his car at his Rustenburg home.

Who is to blame for Phakoe’s death? Wolmarans, yes. His bodyguard, Enoch Matshaba, certainly. But what about all the other ANC leaders who were warned about the Wolmarans problem and did nothing or tried to find a “political solution” for it? What about those people in the SAPS who failed to investigate properly? And what about Richard Mdluli, in whose office the investigative file on the Phakoe murder was found? What about those politicians who have tried everything to protect the very Mdluli? Are they all blameless? And are they – just as much as Mr Wolmarans – not responsible for the fact that the cancer of corruption and nepotism has taken hold in many municipalities, negatively effecting service delivery and leading to a breakdown in trust between voters and their local representatives? Who exactly have blood on their hands in this case?

These are the questions that Gwede Mantashe and other ANC leaders have to grapple with as they try to fall asleep at night.

BACK TO TOP