Quote of the week

[T]he moral point of the matter is never reached by calling what happened by the name of ‘genocide’ or by counting the many millions of victims: extermination of whole peoples had happened before in antiquity, as well as in modern colonization. It is reached only when we realize this happened within the frame of a legal order and that the cornerstone of this ‘new law’ consisted of the command ‘Thou shall kill,’ not thy enemy but innocent people who were not even potentially dangerous, and not for any reason of necessity but, on the contrary, even against all military and other utilitarian calculations. … And these deeds were not committed by outlaws, monsters, or raving sadists, but by the most respected members of respectable society.

Eichmann in Jerusalem: A Report on The Banality of Evil

Boston bombing shows we see the world from US perspective

A bomb explodes in a far-off land and three people die tragically. For several days our newspapers carry detailed stories – often on their front pages – telling stories of the heroism of survivors, the tragedy of those maimed and killed and the intense hunt for the killers. The people they report on come alive before our eyes because they are treated as human beings with hopes and dreams, capable of feeling pain and of joy, disappointment and fear. They are American and we feel we know them even if we have not (yet) fully become like them.

In the same week a suicide bomber blows himself up inside a café in another troubled land, killing a least 27 and wounding dozens more. You wait in vain for stories of heroism and tragedy of that event to be published on the front pages of our newspapers. But these victims are not given any voice, are in fact not treated as human beings with names and faces and lives shattered by “terrorism”. They are Iraqi’s and we can never know them because we are not told their nuanced and complex stories and so they are forever destined to remain Other to us.

It is not as if we have not heard of Iraq. When the Americans invaded that country under a spurious pretext, Iraq was on the front pages of all the newspapers. Some of us even know where to find it on the map. But the Iraq story is not treated as if it is our story. Iraqi victims of American terror are not turned into human beings, but, at best, are depicted as symbols devoid of any flesh and blood and feelings. It is assumed we are not interested in human beings living far away unless they appear as American soldiers and American journalists on American news programmes – and maybe we are not. Neither are we apparently interested in the shocking report of fighting in Nigeria (killing up to 190 people in the past day) or strife in Somalia. We are sometimes told about these “trouble spots”, but the “trouble” is never given a human face.

Unlike the people of Boston who are treated as our family and friends: real people with real feelings and real humanity. No wonder many of us seem to care more about three people dying in Boston than 27 people dying in Iraq or almost 200 people being killed in Nigeria. How are we supposed to care about people in Iraq and Nigeria if we are seldom if ever told who they are; why they are sad or angry or happy; why they cry and why they laugh; what food they like and which shops they hang out in? We are not even told whether these countries have a stock exchange and whether the prices on that stock exchange have gone up or down. As far as we can tell, people living in Iraq or Nigeria do not matter.

If we did not know any better it would have been easy to believe that rich people in so called developed countries; people who speak English; people with quick access to the internet and cell phones, whose lives become real because we see them weep and laugh for the cameras after every minor tragedy; people living in countries dominated by the descendants of those who colonized us; that such people are the ones who we are supposed to emulate and whose cultural habits and attitudes we will (hopefully!) one day be able to imitate perfectly. Then we will also be “civilized”. But surely we do – we must – know better than believing this?

In a confusing week in which we are told more about the lives of a few people living in far-off Boston than we have ever been told about people living on our own continent, I have to wonder: who are we and what have we become? What are the meaning-giving stories embedded in our beings that help us make sense of the world around us and of where we belong in this world? Who gets to tell these stories and what are the (often unspoken and unexamined) assumptions on which those who select and tell these stories base their decisions? Are we really no more than confused, second-rate, American wannabe post-colonials who have bought into the idea that our worth is measured by how well we can manage to imitate the cultural practices, attitudes and habits of a fading neo-colonial power – albeit one who has elected a “black” president?

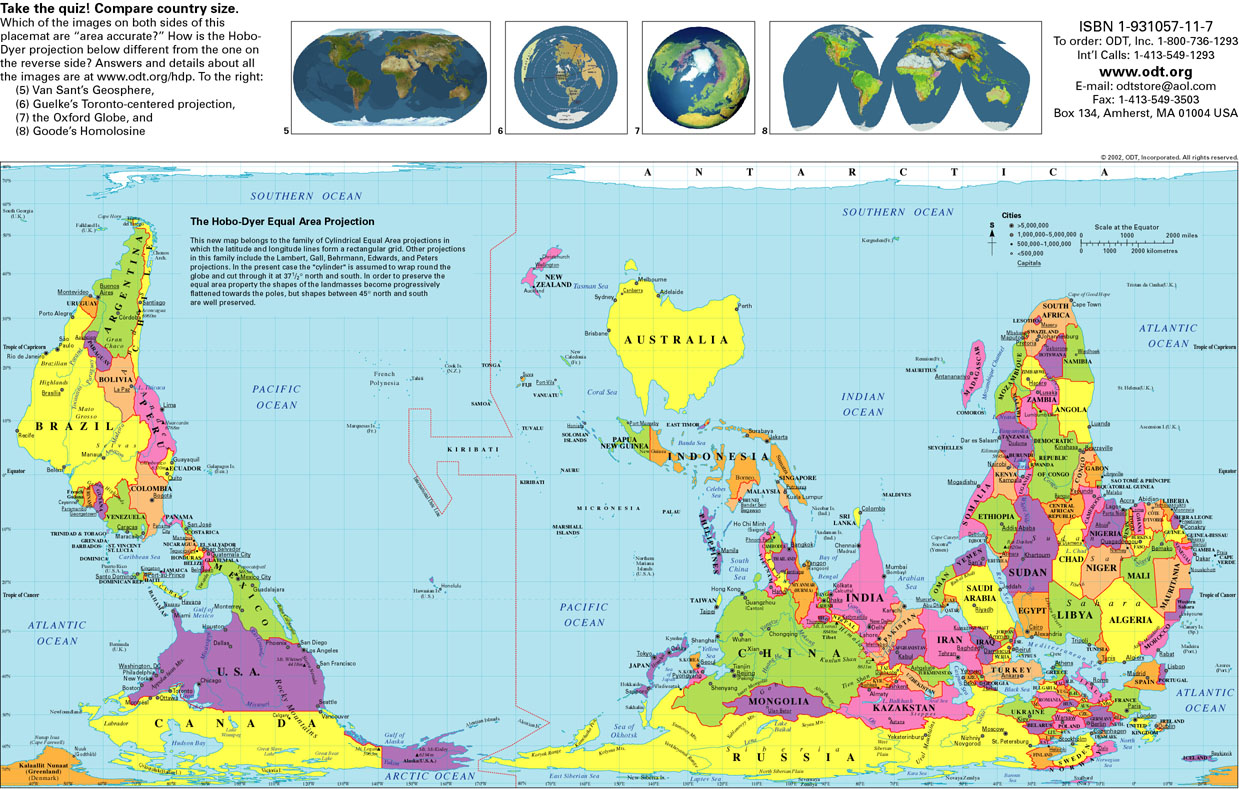

In 2001 I attended an exhibition entitled The Lie of the Land – The Secret Life of Maps. Ironically, I attended this exhibition – if I remember correctly – in London at the British Library, a magnificent creature born out of the most colonial of institutions – the British Museum. Although the exhibition was not without its faults, it provided an arresting visual critique of Eurocentrism, showing how the worldview of dominant cultural and economic groups from the Northern hemisphere influence the way in which most “standard” – supposedly “apolitical” and “objective” – maps are rendered today.

For example, on most maps, Europe and North America are situated on top – allowing us to believe that these countries are really “on top of the world”. Africa, Australia and South America are always situated at the bottom. Why never the other way around? Cartographers make assumptions about the world (North is assumed to be at the top) and these assumptions have become normalised and are viewed as “common sense”.

But these politically embedded assumptions help to structure how we see the world and our place in it. Few of us ever stop to think about the politics of cartography and what it says about Western cultural and economic imperialism and domination. Few ever think how these unexamined assumptions structure the way we see ourselves, to what extent and on what basis we rate our own worth (or supposed, entirely imagined, lack thereof) or how it restricts our imagination and limits the ways in which we think it is possible to excel and thrive in this world.

Most South Africans (obviously excluding those with British passports) live in an in-between world: between their own lived reality and the images (presented as idealised and worthy of emulation) they see on television and in the printed media. This is not a comfortable space to be in. For many South Africans who were not born into the dominant colonial culture or have not managed to assimilate into this dominant colonial culture (through education based on the values and assumptions of the colonial powers, by watching soap operas on TV, by singing along to Western pop music, by paging through magazines in which white people from America and the USA are depicted as the height of beauty, glamour and style), the country can feel like a foreign place.

Not that it is possible or desirable to turn the clock back. We cannot undo the effects of colonialism. Nor can we entirely escape the conquering power of Western culture and economic and military dominance of a superpower like the USA. We all have a bit of American DNA in our identities now – whether we like it or not. The milk (slightly sour milk perhaps?) has been poured into the coffee and cannot be removed. The media (and many of our politicians and educators) are telling us that the sour coffee is delicious and good for us. Drink up and ask for more! But, why should we drink this putrid concoction? Why not mix that concoction into a cake mix and bake a delicious coffee cake with it?

The problem is that our media (often politicians and professors, too) are only dimly aware (or not aware at all) that they are steeped in the values (and necessarily view the world through) the eyes of the old and new colonial masters. They never ask whether Europe, figuratively speaking, should really be at the top of the map and whether it is not time to flip the map around, the right side up, with Africa proudly right in the middle and at the top.

Even when they tell diverse stories about many different South Africans, even when they engage with diverse opinions from a wide spectrum of opinion makers, newspapers and politicians and academics seldom tell these stories or view these opinions in ways that even attempt to escape the framing assumptions of the culturally dominant colonial culture.

I suspect many readers of this column will be outraged or perplexed. Some would not be able to articulate why they find nothing wrong with the overheated reporting of the death of three Americans, as compared to the almost invisible treatment of our fellow human beings living in Iraq and Nigeria. Others will conjure up arguments that affirm the basic premise of this piece: arguing that there is nothing new about people getting killed in Africa or the Middle East, while the bombing of a road race in pristine Boston is shocking – not realising that by stating this they are affirming their inability to see most people on our planet as living, breathing human beings.

No wonder, because how can we grieve for 180 dead Nigerians when we are not told the names of those killed, when (even if we tried) we would not be able to find out what their families felt about their killing, whether they were doing the dishes or making love when they heard the news; whether the curtains were drawn when the police officer arrived to bring the sad tiding; whether any heroes saved some of the victims; which hospitals the survivors were rushed to and what the name of the doctor was who operated on the little boy who miraculously survived the shooting. Because we are not presented with the details that would enable us to imagine the real lives of our fellow Africans (often those details are missing about stories closer to home too), we are stuck with our obsession about and our sympathy for others we probably have less in common with.

BACK TO TOP