Quote of the week

[T]he moral point of the matter is never reached by calling what happened by the name of ‘genocide’ or by counting the many millions of victims: extermination of whole peoples had happened before in antiquity, as well as in modern colonization. It is reached only when we realize this happened within the frame of a legal order and that the cornerstone of this ‘new law’ consisted of the command ‘Thou shall kill,’ not thy enemy but innocent people who were not even potentially dangerous, and not for any reason of necessity but, on the contrary, even against all military and other utilitarian calculations. … And these deeds were not committed by outlaws, monsters, or raving sadists, but by the most respected members of respectable society.

Eichmann in Jerusalem: A Report on The Banality of Evil

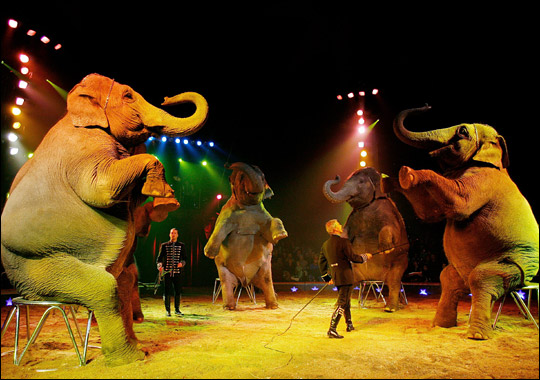

Animal antics and the separation of powers doctrine

Few people in South Africa are probably aware of the existence of the Performing Animals Protection Act of 1935. Until last week I sure was not aware of this Act. The Act requires anyone “intending to exhibit or train for exhibition any animal, or who uses a dog for safeguarding,” to apply for a licence to do so. The application must be considered by a magistrate, who must issue the licence if he or she is satisfied that the applicant “is a fit and proper person”.

Last week in National Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals v Minister of Agriculture, Forestry and Fisheries and Others the Constitutional Court (in a unanimous judgment written by Justice Raymond Zondo) confirmed that the provisions of the Act requiring a magistrate to grant such a licence was unconstitutional because it infringed on the separation of powers doctrine.

Despite the novel nature of the legal provisions at play, the judgment will probably become a classic (and much prescribed) one as it comprehensively and succinctly summarises the Constitutional Court’s approach to the separation of powers as it relates to the judicial branch of government.

As the Court pointed out, the separation of powers doctrine is not a fixed or rigid constitutional doctrine. There are many different models of separation of powers in the world. More specifically, our Constitution does not provide for a total separation of powers among the Legislature, the Executive and the Judiciary.

It is not surprising that the Act – passed way back in 1935 – requires magistrates (as opposed to a government agency) to grant licences to anyone intending to exhibit or train for exhibition any animal, or who uses a dog for safeguarding.

Until 1991, there was little or no separation between the lower courts and the executive in South Africa. Magistrates were employed as civil servants and had little or no independence. They were required to perform many administrative functions. The Apartheid government also relied on magistrates to lend a veneer of legitimacy to otherwise highly politicised decisions.

For example, magistrates often had to chair inquests into the death of political opponents of the Apartheid regime who died in police custody. In probably the most shocking and notorious case, the presiding magistrate in the Steve Biko inquest found that “no act or omission involving an offence by any person” was responsible for the death of Steve Biko – despite the fact that overwhelming evidence emerged during the 15-day inquest that the then security police had tortured and killed Biko.

This all began to change in 1991, when legislation was passed formally to separate the magistracy from the executive. In the democratic era, under the separation of powers doctrine, it would be unthinkable for either judges or magistrates to be as closely aligned to the executive as magistrates were prior to 1991. As the independence of the judiciary is now constitutionally guaranteed, the separation between the executive and the judiciary it is now a constitutional imperative.

This does not mean that either judges or magistrates can never fulfil non-judicial tasks. In some cases, judges (even those who have not retired) may chair commissions of inquiry. Judges also serve on the Judicial Service Commission (JSC) and magistrates and judges fulfil other administrative tasks related to the running of the courts.

As the Constitutional Court once again pointed out, there are:

difficulties confronting government in attempting to carry out its constitutional mandate to transform our society, to the extensive demands made upon it in relation to basic needs such as housing, health, education and social welfare and to the need to make prudent use of scarce resources. There may be reasons why existing legislation that makes provision for administrative functions and duties to be performed by magistrates is necessary, and is not at present inconsistent with the evolving process of securing institutional independence at all levels of the court system.

The Court recognised again that there are differences between the lower courts and the high courts and that lower courts need not enjoy exactly the same degree of independence and separation as the high courts. It might therefore be legitimate for magistrate to perform certain administrative functions but unjustifiable for a judge to perform the same function.

What will offend the separation of powers is the performance by a magistrate of administrative duties unrelated to his or her judicial functions in circumstances where there is no justification for that non-judicial function to be performed by a magistrate in that, for example, it can be performed by a non-judicial officer, e.g. an officer or official in the public service, without much difficulty. However, the performance by a magistrate of a non-judicial function unrelated to his or her core functions where that can be justified does not offend the separation of powers.

In this case, a decision to grant a licence to a person who wishes to train or exhibit an animal would clear be a non-judicial function not closely connected with the core function of the Judiciary. After all, although many Magistrates might have exceptional abilities as judicial officers, it is unclear how their training and knowledge would help them to decide whether to grant a licence to a circus owner who wishes to have lions perform in her circus.

In this case there was no compelling reason why a non-judicial function which is not closely connected with the core function of the Judiciary should be performed by a member of the Judiciary and not by the Executive or a person appointed by the Executive for that purpose. As Zondo pointed out:

I do not see why, if, for example, a non-judicial body or officer can be given the power to issue casino or liquor licences, a judicial officer such as a magistrate should be assigned the function of issuing animal training and exhibition licences. If we were to hold that it accords with this country’s model of separation of powers for a statutory provision to require a member of the Judiciary to issue animal training and exhibition licences and that does not offend the separation of powers, where will the requirement for the performance of administrative functions by magistrates stop?

The case did not deal with the more philosophical issues regarding the inconsistent manner in which our law deals with the treatment of animals. However, the case does contain a very robust defence of the constitutional imperative of maintaining a clear separation between the judiciary and the other branches of government. As such, it illustrates that the Constitutional Court is prepared to hand down judgments that jealously guard its independence.