Quote of the week

When a foreigner resides among you in your land, do not mistreat them. The foreigner residing among you must be treated as your native-born. Love them as yourself, for you were foreigners in Egypt. I am your God – Leviticus 19:33-34.

Consequently, you are no longer foreigners and strangers, but fellow citizens with God’s people and also members of his household, built on the foundation of the apostles and prophets, with Christ Jesus himself as the chief cornerstone. In him the whole building is joined together and rises to become a holy temple in the Lord. And in him you too are being built together to become a dwelling in which God lives by his Spirit – Ephesians 2:19-22.

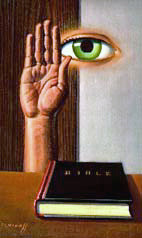

Christian Bible

Why President Zuma is like Tretchikoff

This past weekend I viewed the Vladimir Tretchikoff exhibition at the National Gallery in Cape Town. What a weird and unsettling experience it was. Some pictures are charmingly and gratifyingly kitsch, while others – like the series of the ten commandments (“though shalt not steal” and “though shalt not bear false witness” reproduced below for your viewing pleasure) – I found so hideous and so badly painted that I had to flee the room. Yet, prints of these paintings, like prints of many of Tretchikoff’s other works of “art”, have sold millions of copies all over the world and made the Russian artist (who had settled in South Africa after the war) a rich man.

How could this be, I wondered. Surely one does not have to be an art lover to see how bad, tasteless – even ugly – most of these paintings are? After all, most credible critics have panned Tretchikoff’s work and have been horrified that it has remained so popular with the general public – despite the fact that it is so bad and so tasteless.

Which brings me to Jacob Zuma, who in many ways resembles the late Tretchikoff. Both are really bad at what they do but remain relatively popular. Both have done rather well financially because of what they do best (painting kitsch Javanese women for Tretchikoff, singing and dancing for Zuma). Both can pull a few tricks out of the hat to please the crowds. Both have been panned by the “critics” and shunned by the chattering classes. And the careers of both can be explained with reference to their tumultuous pasts.

It is now widely accepted amongst the chattering classes that President Jacob Zuma’s first term as President of South Africa has so far been less than inspiring, even disastrous. This view has become accepted wisdom, not only amongst the chattering classes, but also amongst many political role players from both the left and the right.

The consensus seems to be that President Zuma might well be charming and affable but that, as President of the country, he is intellectually out of his depth, lacking in vision, unprincipled, indecisive, paralysed by fear, paranoid and rather lackadaisical about reining in corruption and nepotism in government and in the ANC. Like Tretchikoff he might be popular with the anti-intellectual crowd while being really bad at what he is doing.

Supporters will argue that President Zuma is still quite popular, especially in KwaZulu/Natal, and that he should be given a chance to show what he is made of. Much like supporters of Tretchikoff point to his popularity with the masses of our people, so Zuma’s supporters will argue that he has a remarkable knack to please many different people most of the time. If he happens to have disappointed the chattering classes and anyone with even a smidgen of insight, so be it, they might argue, because in the end he gives the people what they want. He might not actually be able to govern the country but he can dance and he can sing a mean Umshini Wami, which he does at the drop of a hat before jetting off to some exotic location or going for one of his regular rests at Nkandla.

Watching the documentary film currently showing at the National Gallery about Tretchikoff’s life, it struck me that – like President Zuma – much of Tretchikoff’s work and his need to be popular and make money can be explained with reference to his early life. Tretchikoff was the youngest of eight children in a wealthy family and grew up in Siberia. Upon the Russian Revolution in 1917, the family abandoned their property and fled to China.

Watching the documentary film currently showing at the National Gallery about Tretchikoff’s life, it struck me that – like President Zuma – much of Tretchikoff’s work and his need to be popular and make money can be explained with reference to his early life. Tretchikoff was the youngest of eight children in a wealthy family and grew up in Siberia. Upon the Russian Revolution in 1917, the family abandoned their property and fled to China.

During the Second World War Tretchikoff, who then lived in Singapore, was on board a ship evacuating ministry personnel to South Africa. The ship was bombed by the Japanese, and the 42 survivors rowed first to Sumatra, which they found was already occupied by the Japanese Army. They then rowed to Java, which took 19 days, only to find that it too was occupied.

Tretchikoff spent the rest of the war in a Japanese prison camp (where he spent three months in solitary confinement for protesting that as a Russian citizen he ought not to be imprisoned), and then on parole in Batavia, (now Jakarta), where he worked with a Javanese dance troupe. Here he met Leonora Schmidt-Salomonson (Lenka) who became his lover and one of his most famous models. In 1946 he was reunited with his wife and their daughter Mimi in South Africa (they had been successfully evacuated on an earlier boat). Apart from the fact that this history suggests that Tretchikoff – like Zuma – had an eye for the ladies, this rather “exotic” and unstable history might explain why Tretchikoff painted such garish pictures and was so determined never to be poor again.

Jacob Zuma, of course, never got the opportunity to study past grade 5 and grew up poor in a rural area where – as he confessed in another moment of weakness – he would assault gay men if they ever revealed themselves to him. He became President of South Africa after serving a long prison term on Robben Island as a political prisoner, before going into exile during the dark apartheid years. He was made Deputy President of the ANC (and then the country) because Thabo Mbeki thought that he did not have political ambitions.

After his friend Schabir Shaik was convicted of bribing him, he was fired from his job as Deputy President. He was then charged with corruption and bribery and only escaped prosecution because the Acting National Director of Public Prosecutions conjured up some strange reasons to drop the case against him.

Zuma is in many ways an accidental President who lacks the obvious gravitas, inquisitiveness and intellect one would associate with a President of an important mid-sized country like South Africa. But in a strange kind of way, Jacob Zuma had no choice in the matter: he was either going to become President or he was probably going to go to prison, so in order to survive he had to protect himself and had to make sure that he became President of the ANC. When he became President of the country, criminal charges against him had been dropped, but it is not far-fetched to speculate that President Zuma had been seared by this fight for survival and that his actions as President have been shaped in large part by this feeling of constantly being under threat.

Can one not argue that because of the manner in which Zuma became President of the ANC and the country, almost every move he makes as President is based not on what is best for the ANC or the country, but on what would best secure his own survival and protect him from plots and from attacks? Surely President Zuma’s reluctance to take a stand on almost any issue stems from his fear of alienating various factions in the ANC, whose support might be needed (along with sufficient funds) to insulate him from any prospective threats of criminal prosecution.

When his own survival has not been at stake, President Zuma has made some good appointments. For example, he has appointed Aaron Motsoaledi as Minister of Health and we are now beginning to see what a difference a sane and sober Minister can make to his or her portfolio.

But when President Zuma has been required to appoint those people who could protect him in future and could secure the financial future of him and his family, he has failed dismally to act wisely or selflessly. First, there was the appointment of National Director of Public Prosecutions (NDPP), Menzi Simelane, who has shown a cavalier attitude to the truth and a lack of respect for the Constitution. But Zuma had to appoint a person as NDPP who would be trusted to be blindly loyal – just in case those corruption charges are ever resurrected (or in case new corruption charges are brought based on his friendship with the Gupta’s).

There were the small “mistakes” of appointing Geoff Doidge as Minister of Public Works and Barbara Hogan as Minister of Public Enterprises, both departments that oversee – directly or indirectly – billions of Rand in state spending on leases, construction and maintenance, but those small “mistakes” were quickly corrected.

Bheki Cele, an old friend who seems to have some difficulty with grasping the finer points of ethics in administration and of respect for human rights (no need for police to respect the “innocent until proven guilty” mantra when they can just kill the suspects), became Police Chief while old friend Siyabonga Cwele became the Minister of State Security. All these appointments had one thing in common: good and trusted friends were appointed to positions not because of their skills, honesty and vision but because they could be trusted and because these positions needed to be in the right hands to ensure that President Zuma is protected from any possible future legal trouble.

Might Zuma’s tenure as President still be salvaged? After all Vladimir Tretchikoff – whom no reputable art gallery ever wanted to exhibit during his lifetime – is currently being exhibited in South Africa’s National Gallery. And although most of us in the chattering classes still think that he is an unremarkable painter, some of us would consider hanging Tretchikoff’s “Green Lady” in our homes (perhaps positioned next to three lovely porcelain ducks flying into the sunset), to show our appreciation – in an ironic sort of way, of course – for this kitsch artist.

Who knows, one day long after his tenure as President has come to an end, some of us in the chattering classes might yet raise an ironic cheer to Jacob Zuma – the ultimate survivor and lover of women. Let’s face it, amongst the chattering classes, fads and fashions change fast, so if only our President could get his paranoia under control, he might still emerge as a President who did better than we expected of him.

BACK TO TOP